“I lost all my memories. My family retaught me who I am,” says Jørgen, an Utøya survivor

“One of my reactions to that day was that I lost my memory from ages one to seventeen. My actual memory starts on 22 July, 2011,” explains Jørgen, a young lawyer who survived the attack on the island of Utøya. “Most of my life, who I was and how I felt about things got wiped out. What I have from before are just recollections from photos and stories from families and friends.”

The trauma of that day robbed Jørgen of not only his memories, but also his feelings and emotions. “It essentially makes you feel like a monster, because you are supposed to feel stuff, right?” he asks rhetorically. “For a couple of years, I didn’t feel hungry. I ate, because I was supposed to. I laughed, because I was supposed to. I got really good at learning what to do in social settings. But I did it because I was supposed to, not because I actually felt it,” he reveals. This loss of emotions and memories also upset his relationships with his close friends. For them, he wasn’t the same Jørgen anymore. They didn’t recognize him. And he certainly didn’t recognize them.

That was just part of it. After returning to his home town, Jørgen faced another challenge: dealing with the attention. At the first meeting of the local survivors, the entire town showed up. Their homes were flooded with roses. The support was simply enormous. Jørgen admits that it was bizarre, but not unpleasant. Until it started to be. “Whenever I came into a store – and this happened for at least a year after – I saw it in everyone’s eyes. When they saw me, they saw trauma. It feels so bad seeing everyone look at you with pure sadness in their eyes. When you are trying to move forward, it hinders that whole process,” he admits.

On the afternoon of July 22nd, 2011, the roughly-thirty-year-old Norwegian far-right extremist Anders Behring Breivik detonated nearly a ton of explosives in a white van parked in the government quarter in the center of Oslo. He killed eight people. Less than two hours later on the island of Utoya, amidst a summer camp organized by the youth wing of the then-ruling Labour Party, he shot dead 69 young people.

According to Jørgen, the rhetoric of the Norwegian government and media determined how survivors were supposed behave. “Your natural reaction to being shot at is extreme anger. At the same time, we were told by the press, politicians and other people that we should meet hate with love. Which is a wonderful sentiment, but I was just mad,” says Jørgen. “He tried to kill me. He killed friends of mine. What is the natural reaction to that? You just want to be angry and get revenge. But our trauma response was dictated by what the people said we were supposed to feel. We were supposed to meet hate with love. Which was hard. But we did, in some way,” he laughs.

What was it like for Jørgen to live without memories and emotions? How did others treat him? And why is he uncomfortable with being seen as just a survivor of one of the most infamous terrorist attacks in history? This and more on Episode 6 of the seven-part podcast series Surviving Utøya and Oslo.

The series was created in cooperation with the production company Subjektiv, with the support of the Norway Grants and in partnership with the 22 July Center in Oslo.

Nejposlouchanější

Více z pořadu

Mohlo by vás zajímat

E-shop Českého rozhlasu

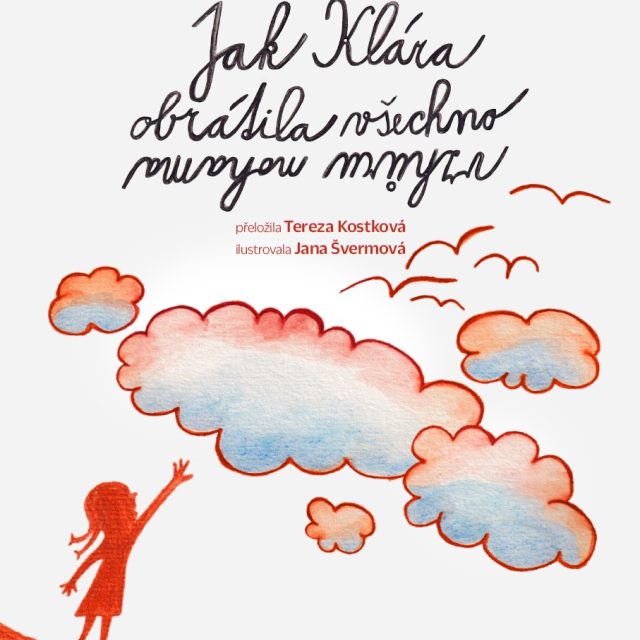

Kdo jste vy? Klára, nebo učitel?

Tereza Kostková, moderátorka ČRo Dvojka

Jak Klára obrátila všechno vzhůru nohama

Knížka režiséra a herce Jakuba Nvoty v překladu Terezy Kostkové předkládá malým i velkým čtenářům dialogy malé Kláry a učitele o světě, který se dá vnímat docela jinak, než jak se píše v učebnicích.